“Not interested.” That’s the response I received from a man who opened his door to me as I was canvassing for Christy Clark, a candidate for North Carolina’s House District 98. I had been looking for his daughter, a newly-registered voter, but I found only him. His curt response as he shut the door — both on me and on his daughter’s political power — was one of many obstacles to voting that young people face from older generations in the United States today.

Voter disengagement in the United States is a national problem with broader implications for political representation. U.S. voter turnout consistently lags behind that of peer industrialized democracies around the world. And civil liberties in the U.S. lag behind similarly: there are 38 developed countries that outpace the “land of the free” in this category, according to Freedom House.

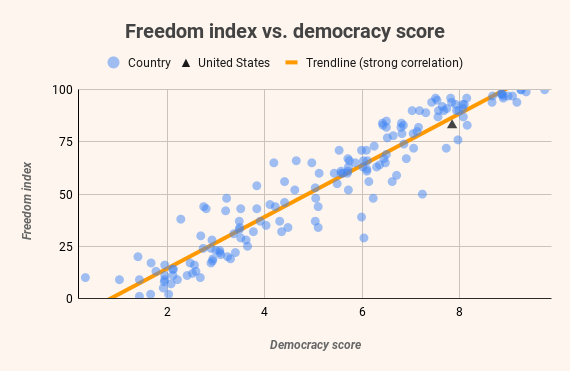

Our analysis confirms that independently-evaluated democracy is firmly correlated with civil liberties in 162 countries for which data is available.

Young people turn out to vote even less than older Americans, which can minimize our collective power. But is this a problem of political apathy? Many of the young people I know are more engaged in politics than their elders; there’s a reason that, in recent years, youth have been the ones leading activist movements like those for climate action and gun reform. Perhaps the problem is not our apathy at all.

Indeed, a FiveThirtyEight/Ipsos poll conducted in 2020 found that young people were more likely to face many significant barriers to voting than their older counterparts. Eligible young voters were more likely to have to wait for more than an hour at their polling place, to have to work during polling hours on election day, to miss the deadline to register to vote, to not receive their absentee ballot in time to vote, and to be told they weren’t eligible to vote at their polling place.

It’s not easy to register to vote: those who wish to do so have to complete and mail paperwork or go to a Department of Motor Vehicles office, which is always a hassle. Registration ahead of time is a prerequisite to voting in North Carolina. This creates a barrier for young people in particular, who may be unaware that the registration process exists at all. Despite this, the civics curriculum for high school in the state includes no standard to inform students about important topics like how they can become eligible to vote. Teaching students that voting is a civic responsibility is useless if the class doesn’t also teach them how to do it.

The systemic suppression of the youth vote means that politicians can continue to ignore the issues that are more important to young voters, like mitigating climate change, preventing gun violence, and ending police brutality.

Fortunately, there’s a way to fix this. Young voters are becoming an increasingly powerful constituency of voters in the U.S., and it’s becoming harder for politicians to ignore the issues important to them as a result. If every current North Mecklenburg student voted, we could make up 10% of the Huntersville electorate by 2026.

That makes it crucial that every young person eligible to vote is able to do so. That begins with registration: if you’re going to the Department of Motor Vehicles to get a permit or license, say yes when you’re asked whether you want to pre-register to vote. Doing so will automatically make you eligible to vote in the next election after you turn 18. If you aren’t going to the DMV, you can register to vote in a voter registration drive or online at turbovote.org.

After you register, make sure you know when and how to vote. Election Day always falls on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November. In 2023, that day will be November 7; in 2024, a presidential election year, it will be November 5. Another option is to vote early, which lasts for seventeen days and ends on the Saturday before Election Day; voting early usually results in less time spent waiting at the polls.

Before you go vote, make sure you know about the candidates. Read biographies published in local newspapers or the candidates’ websites to learn more about how they will advocate for you. Make sure you cast not only a vote, but an educated one.

It takes all of us to make a difference. Youth voters have the potential to be the most politically powerful group in the country, but we all must do our part. 🆅

The opinions expressed within this piece are solely the author's and do not necessarily reflect the opinions and beliefs of North Mecklenburg High School or the Viking Voice.